Hearing loss is one of the risk factors for dementia, which is the impaired ability to remember, think, or make decisions that interferes with doing everyday activities. Alzheimer’s disease is one type of dementia. Some studies show that treating hearing loss with hearing aids can reduce cognitive decline. Thus, it is important not to ignore your hearing health especially as you age. This page offers a review of the science on hearing, hearing aids, and dementia — as well as number of useful resources to learn more.

PROJECT

Hearing, Hearing Aids,

and Dementia

HUMAN HEALTH

PROJECT

Hearing, Hearing Aids,

and Dementia

HUMAN HEALTH

Project summary

Background

- Presbycusis is the technical name for hearing loss that occurs gradually as people get older. Almost half of the people over 75 years have trouble hearing and it is more common in men than women.

- Hearing loss is a modifiable risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease associated with 8% of global dementia cases.

- Hearing and brain health is tightly connected. Loss of hearing can impair social interactions and can delay diagnosis and treatment of dementia.

Key points

- While the results of studies vary, hearing treatment may reduce cognitive decline in some individuals. Improved hearing can also impact quality of life, reduce social isolation, and improve communication with healthcare professionals.

- A 2023 research study reported that moderate to severe hearing loss was associated with a higher prevalence of dementia compared to people with normal hearing. Hearing aid use was associated with a lower dementia prevalence.

- A meta-analysis found that hearing aids were associated with a 19% decrease in the risk for long-term cognitive decline.

Parsemus' role

- The Parsemus Foundation has supported research on Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, as well as advocating for a focus on prevention.

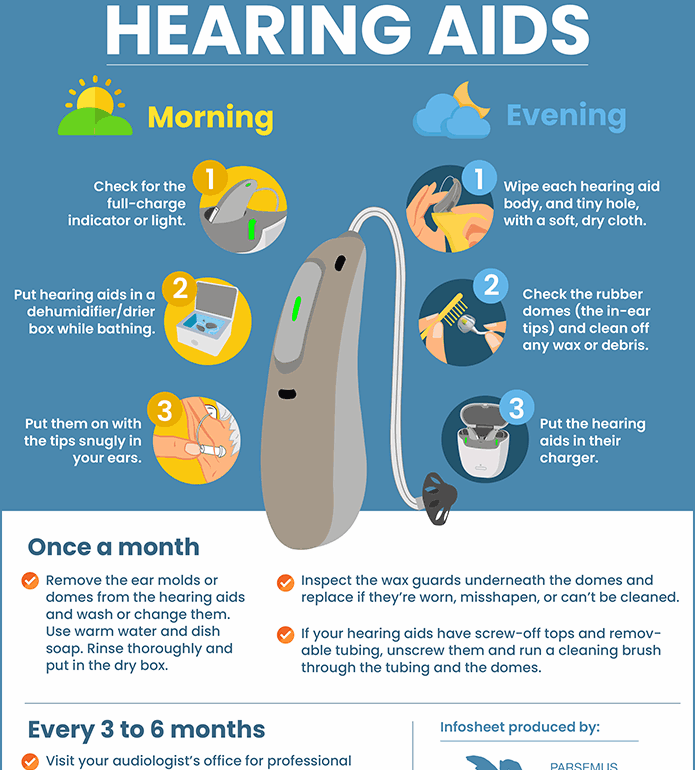

- The foundation has also created a detailed handout on the care of hearing aids for users.

Related projects

Preventing dementia

Click the image to see the full infographic

Dementia involves the degeneration of brain neurons. There are different types of dementia, with the most common being Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and vascular dementia. Each type of dementia involves different changes in the brain and symptoms (see infographic above).

Risk factors for dementia include less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, low social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution.

Many of these are modifiable risk factors, meaning that we can take action to address the issues to help prevent dementia.

Dementia and hearing loss worldwide

Hearing loss has been proposed as a modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. A 2020 report indicated that hearing loss alone is associated with 8% of global dementia cases.

How does hearing loss relate to cognitive impairment?

• Hearing loss can limit social engagement, which is also a risk factor for dementia.

• The inability to hear well can make the diagnosis of dementia more difficult or delay diagnosis and treatment.

• Hearing impairment at midlife has been associated with steeper temporal lobe brain volume loss (Livingston, et al. 2020).

• Cognitive impairment can reduce compliance with the use of hearing aids (Dawes, et al. 2015).

• Neurodegeneration due to dementia can influence the brain’s ability to process sounds.

The complicated process of hearing

Hearing involves much more than the ears. Yet, most hearing tests evaluate the function of the ears and associated structures for the ability to detect specific soft tones. Thus, the identification of deafness involves these “peripheral” hearing mechanisms.

On the other hand, “central” hearing involves the brain. Studies tell us that different structures in the brain work together to make something meaningful from the sound waves that the ears pick up. This complex task includes multiple steps, such as the ability to detect specific sounds from background noise, categorize and understand the sounds, and create an appropriate behavioral response. The peripheral and central hearing mechanisms work closely together and involve both ear and brain structures.

The chicken or the egg?

The concept that we can reduce the risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, by treating hearing loss is reassuring. However, scientists now know that the relationship is not as simple and straightforward as originally thought.

Most studies finding an association between hearing loss and the development of dementia have measured our ability to detect soft tones. Less consideration has been given to the central hearing process in the brain. Yet, the process of hearing is highly susceptible to neurodegenerative disease. In fact, different types of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementias, and Lewy body disease, are associated with different hearing impairments.

So, the question arises, does cognitive decline result from hearing loss affecting the brain, or does neurodegeneration in the brain affect hearing? This classic “chicken or the egg” dilemma doesn’t have a simple answer. Long-term research on hearing aid use supports the concept that hearing loss has effects on cognitive decline. But some scientists argue that more attention should be given to the central brain mechanisms on the expression of hearing loss with dementia.

The impact of hearing aids

on dementia

More research is needed to fully understand the relationship between cognitive decline and hearing loss. But research on the treatment of hearing loss with hearing aids offers a method to prevent or reduce the risk of dementia.

A 2023 study included 2413 individuals in the U.S. who were over 65 years. The researchers reported that moderate to severe hearing loss was associated with higher prevalence of dementia compared to people with normal hearing. Hearing aid use was associated with a lower dementia prevalence.

Research on hearing aids and cochlear implants has offered some hope for improvement in cognition, although individual studies have reported diverse findings. A 2023 meta-analysis reported that across 31 multiple studies, hearing aids were associated with a 19% decrease in the hazard for long-term cognitive decline, and a 3% improvement in cognitive test scores in the short term for cochlear implants. The authors concluded that reducing cognitive decline by improving hearing could be due to lessening the cognitive burden from listening, increasing sensory stimulation and reducing atrophy of affected tissues, and reducing social isolation.

Of significance is a recent randomized controlled clinical trial to determine the impact of hearing interventions on cognitive decline. The study was conducted by researchers from Johns Hopkins and published in the Lancet. The scientists reported no impact of hearing aids on cognition over 3 years compared to individuals who received health education alone. However, when considering older individuals with faster rates of cognitive decline, hearing aids provided an almost 50% reduction in the rate of cognitive decline.

More research is needed to fully understand the impact of hearing aids on dementia. However, evidence indicates that hearing treatment may reduce cognitive decline in some individuals. Improved hearing can also impact quality of life, reduce social isolation, and improve communication with healthcare professionals.

Hearing aids for age-related

hearing loss

Presbycusis is the technical name for hearing loss that occurs gradually as people get older. Almost half of the people over 75 years have trouble hearing. It is more common in men than women. Age-related hearing loss generally occurs in both ears and can be so gradual that people affected may not realize it.

Hearing loss can occur due to changes in the inner ear or in the nerve pathways between the ear and the brain. While it is not known why some people have hearing loss and others do not, there are some factors associated with presbycusis:

- Older age

- Being male

- Long term exposure to loud noises

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Medication affecting the sensory cells in the ear (e.g., chemotherapy drugs)

- Genetic predisposition or family history

- Abnormalities in the middle ear

According to the National Council on Aging, common symptoms of presbycusis include:

- Difficulty hearing high-pitched sounds

- Ringing or buzzing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Feeling like people are mumbling or unclear when they speak

- Struggling to hear or understand people in loud spaces

- Unable to hear full conversations on the phone

- Asking people to repeat what they say

- Listening to the radio or television loudly enough that it’s annoying to others

Hearing aids are commonly used to treat age-related hearing loss. In the U.S., hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss are even available over-the-counter. There are a number of different hearing aid types, each with different features and benefits. A qualified physician can assist you in determining the best type of hearing aid for you.

Our guide to caring for hearing aids

Taking care of your hearing aids is important. Be sure to review the instruction manual that came with your hearing aids for brand-specific maintenance details. For general cleaning and care, we’ve created a free, easy-to-follow guide you can download below. Keep it handy—whether on your phone, tablet, or printed out near where you store your hearing aids.

Click on the image to view and download the guide

Take action on

hearing and dementia

If you feel that you may have hearing loss, check out the information from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders on what steps you can take to diagnose and treat hearing loss.

For information on over-the-counter hearing aids available in the U.S., the FDA website has information and Consumer Reports evaluates several brands.

Additional resources

Last updated on March 12, 2025